The cure for colic

When Oliver James's newborn son got colic, he and his wife prepared

themselves for the horror of sleepless nights. Then they attended a

breastfeeding clinic ...

Two weeks after our son Louis was born, three months ago, he started

showing signs of colic. Just when my wife Clare and I were at our most

exhausted, at around six in the evening, he would cry loudly and

inconsolably for no apparent reason, his back arched and his legs

doubled up. Since our daughter Olive (now three) had done the same, we

were not altogether surprised. But we groaned at the prospect of months

of long nights walking him around to no avail and nocturnal drives with

the Pet Shop Boys Introspective album blaring. (This was the only thing

guaranteed to shut our daughter up. Somebody should do a study of which

popular music is most effective in quieting troubled babies - I swear by

the Pets.)

To add to the grief, my wife got mastitis, which we assumed was the

reason each feed felt as if she were having her nipples slashed with

razor blades. The antibiotics to treat it only made our son worse,

upsetting his tummy. As we lurched towards meltdown and bottle-feeding, a

health visitor suggested we visit midwives Chloe Fisher and Sally Inch,

said to be the international queens of breastfeeding, at their drop-in

clinic at Oxford's John Radcliffe Hospital.

That they could help us with the mastitis seemed plausible,

but I was sceptical when Fisher told us that the colic was also to do

with my wife's breastfeeding technique. I had studied the scientific

literature in the past, and despite contact with dozens of health

professionals over the years, and endless discussions with other

parents, no one had told us that colic had anything to do with how you

breastfeed.

About one-fifth of all babies get the full colic syndrome, of whom

only a small minority (5-10%) have any identifiable physical cause. It's

a serious problem because half of those mothers with severely colicky

babies are liable to become mentally ill, falling to one-quarter if the

baby is only moderately colicky (compared with 3% of mothers with none).

The

ailment has baffled medical scientists seeking a biological cause. Only

social, rather than medical, science seems to provide some clues. Most,

if not all, babies in developed nations get some of the symptoms, yet

it is rare or unknown in developing ones. A possible reason is that in

the latter countries, babies are constantly held, fed effectively and on

demand. Babies cry less whose mothers carry them for three hours or

more, or feed on demand during the first two months.

Another reason could be the lack of social support and the

hard-working, stressful lives of pregnant mothers in developed nations. A

study of 1,200 mothers interviewed prenatally and when the child was

three months found that a good relationship with the partner before the

birth reduced colic. Seventy per cent of mothers had colicky babies if

they had a lot of prenatal stress, felt isolated and anticipated needing

a lot of postnatal help, compared with only 25% of babies of mothers

without these problems. Prior problems with the mother's mother also

predicted it. When asked during pregnancy or shortly after the birth,

mothers who recalled distressing childhood memories or expected a lack

of support or excessive interference from their mothers were more likely

to have a colicky baby.

It came, therefore, as a great surprise to me when Fisher told us

that colic in the breastfed baby is primarily due to something as simple

as not attaching the baby to the breast correctly, which means that the

baby is unable to "drain" the breast properly during feeds.

Arriving at the clinic on a Monday afternoon, we were met by the

sight of a clutch of desperate mothers, their babies suckling for

Britain. There were two pairs of twins; our frazzled minds boggled at

the prospect of trying to keep them satisfied. But Fisher and Inch

radiated supreme confidence that salvation was at hand, roving round the

room, providing emphatic instructions.

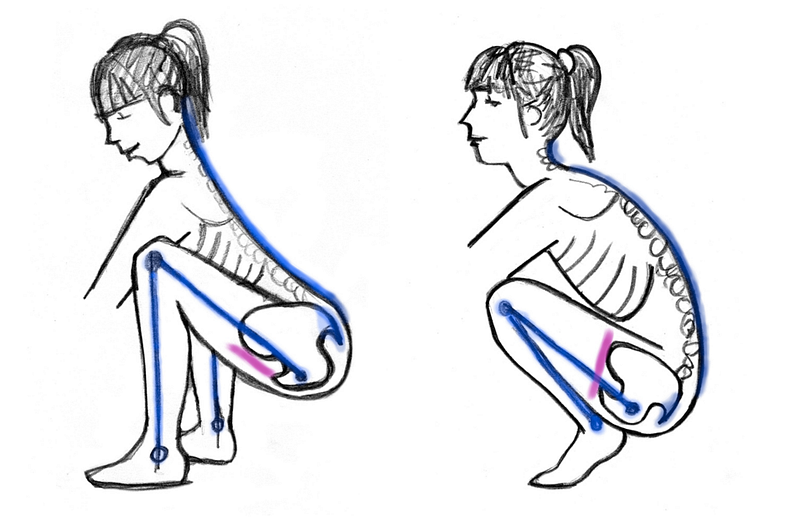

Fisher

enunciated two principles: "First, don't assume the breast is like a

bottle. The milk is in the breast, not in the nipple, whereas with a

bottle, the milk is in the teat. To feed effectively from the breast the

baby must scoop in a deep mouthful of breast, whereas with a bottle, it

can just suck on the end of the teat.

"Second, people wrongly assume the middle of the baby's mouth is

halfway between the top and bottom lip. In fact, the middle is between

the upper surface of the tongue and the upper palate. For the baby to

draw sufficient breast tissue into its mouth, it must be able to get its

tongue well away from the base of the nipple and that won't happen

unless the breast is presented between the tongue and the upper palate."

If the baby did not attach properly, the midwives told us, it would

not drain the breast properly and would keep compressing the nipple

between the tongue and hard palate, turning it into something resembling

minced lamb. Putting this into practice proved surprisingly difficult

but after a bit my wife got the hang of it.

Next came the other important point: "Only switch breasts when the

well-attached baby comes off the breast spontaneously and seems

completely satisfied," said Fisher. "In offering the second breast, let

the baby decide whether he wants it. If the mother starts each feed on

alternate breasts [regardless of whether the baby has had one or two at a

feed], the breasts will get roughly even use. The important thing is to

allow the baby to finish the first breast first."

Failing to do this is the main cause of colic. Fisher also told us

that the initial milk is low in fat and calories. If you switch breasts

before the high-fat milk has been drunk, the baby will take more from

the second breast than he would otherwise have done. Despite the

relatively huge volume of liquid in its stomach, the baby will then be

wanting another feed before long, because low-fat feeds are processed

quickly, leading to a pattern of very frequent feeding. This can cause

mental illness-inducing sleep-deprivation, but worst of all, it will

cause colic.

Both poor attachment and breast switching result in the baby taking

frequent, large-volume, low-fat feeds, which in turn lead to rapid

emptying of the stomach into the large intestine. If too much gets there

too fast, there is not enough of the enzyme lactase to break the sugar

in the milk (lactose) down. The gut turns into a malfunctioning brewery,

with fermentation of the sugar in the excess milk creating gas and

explosive poos. The crying, arched back, rigid tummy and irritability of

colic follow.

I was flabbergasted. If all this were really true, why on earth

wasn't everyone told about it, especially considering the damage done to

the mental health of parents by colic? Fisher replied that she and Dr

Mike Woolridge had published the hypothesis in the leading medical

journal the Lancet 17 years ago. "I was expecting that after that it

would solve the problem. It seems pretty extraordinary to me that it has

not."

Fisher believes she is right because she has seen thousands of

mothers solve the problem by following their advice, but since the 1988

paper, her theory has been scientifically tested. A 1995 study compared

two groups of 150 mothers: one asked to let the baby terminate the feed

on the first breast; the other asked for the baby to feed equally from

both breasts. Twice as many of the mothers who fed equally with both

breasts had colicky babies (23% versus 12%). What is more, finishing the

first breast first resulted in significantly less breast engorgement.

This turned out to apply to us too. Inch doubted that my wife

actually had infectious mastitis or had needed antibiotics for it and

easily proved her point. A few days after my wife had started taking the

antibiotics, the problem had developed in the right as well as the left

breast. Since infectious mastitis is a bacterial problem, and since the

germs should have been killed by the antibiotics, Inch pointed out that

such a transfer could not have happened if it was a bacterial

pathology. Rather, the inflamed breast was due to back pressure within

the ductal system of the breast, she said. Ineffective milk removal was

not keeping pace with milk production so the milk could no longer be

contained within the ductal system. It was forced into the connective

tissue of the breast, where it gets treated as a foreign protein, with

subsequent inflammation and pain.

All

of which proved to be of more than academic interest to us. While we

returned to the Thursday clinic for a booster course in attaching to the

breast, from the first moment my wife did it properly, the pain was

much less. From that very night our son was free of colic and within a

week, the "mastitis" was disappearing.

This is very good news for women suffering the curse of colic who are dedicated breast feeders. I always thought breastfed babies could not get colic. Will pass thin info on to all my new mums.

I can't believe how quick it all was!

I can't believe how quick it all was!